Everyday, in classrooms across the country, many teachers begin their lessons with what are commonly known as Learning Goals, Targets, Objectives or Intentions. John Hattie defines these as “what it is we want students to learn in terms of the skills, knowledge, attitudes, and values within any particular unit or lesson.”

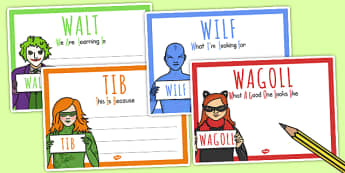

They are usually written on the whiteboard or projected in a PowerPoint slide. Some teachers prefer to use acronyms attributed to formative assessment expert Shirley Clarke, like WALT (“We Are Learning Today”), WILF (“What I’m Looking For”), or even TIB (“This Is Because”) or, in some instances, “WAGOLL” (“What A Good One Looks Like”). Quite often, students are instructed to copy various forms of goals into their books at the start of each lesson. Puzzlingly, some teachers even suggest getting students to recite these goals.

So far, this (mostly) all sounds like common sense; a teacher arrives at class knowing what students will do and learn about. But this practice has grown into a tired, empty routine, which is not only dull and repetitive for students, but now features as a key criteria in most classroom observations. For example, “providing clear learning goals and scales” is a foundation of Robert Marzarno’s popular Art and Science Of Teaching framework, used by eager administrators across the country.

So why is it that with this much explicit sharing of what students will learn and do, students’ engagement and educational performance is actually declining?

An anonymous Head of Department on the Guardian’s Secret Teacher blog suggests it could be that when students enter a classroom, they tend to be “greeted not by an enthralling demonstration or an enthusiastic teacher, but by a whiteboard displaying the outcomes for today, which the teacher will have to read out in order to tick the ‘sharing the learning outcomes’ box on the observation.”

Is it habit that motivates so many teachers to begin a lesson in this way? Or is it fear that a superior will drop by and ‘catch’ them, *gasp*, without an observable learning goal? This endless quest for measurable learning goals in education reveals an unwillingness to embrace the complexities of teaching and the wonder of ambiguity.

Imagine a lesson that begins with no Learning Goal. Does it result in chaos, as the hilarious teacher-made video below demonstrates when, shockingly, no Learning Target is written on the whiteboard when students arrive?

I realize that Learning Goal enthusiasts might ask, “But how will the students know what they’re learning if we don’t tell them?” or claim, “Students must know what they are learning before they learn it – everything must be crystal clear!”

Let me be crystal clear: I am not suggesting that teachers deliberately confuse or mislead students, or turn up at lessons with no clear idea of what is to be accomplished. But it is worth critically examining whether the practice of telling students what they will learn before they learn it equates to the kind of deeper learning that will allow students to thrive in a rapidly changing 21stcentury job market.

Contemporary careers require students to collaborate, wrestle with open-ended problems and think critically and creatively. Accordingly, Jal Mehta states that “both experience and research has told us that teaching is not like factory work, that it requires skill and discretion as opposed to following of rules and procedures.” Indeed, this technique of oversharing technical procedures such as sharing the intention reflects the increasing emphasis in education on accountability, measurement and control.

It is difficult to argue in favour of prescriptive, formulaic Learning Goals when many educational gurus discuss their limitations. Although John Hattie’s research reveals the positive impact of teacher clarity, at no point does his research suggest that every lesson must begin with a teacher-centred Learning Goal. He laments in an interview; “Sometimes I think if I was starting the work again I wouldn’t emphasize learning intentions because too often they become very simplistic and they become almost jingoistic.”

Additionally, Shirley Clarke, who coined WALT and WILF, says that as the popularity of Learning Goals increased, there “appeared a myth that the first words uttered should be the words of the learning objective and it should always be written on the whiteboard before the lesson starts.” Clarke has since distanced herself from Learning Goals, declaring on Twitter that “WALT and WILF died in 2001” after her own studies showed it resulted in children focusing too much on trying to please the teacher. Further, Clarke suggests, “Although the learning objective might be appropriate at the beginning of the lesson (often in mathematics), its appearance before children’s interest is captured can kill their interest.”

Likewise, American author and lecturer Alfie Kohn says Learning Goals “resemble ‘training’ rather than genuine education” and that “even if a teacher has specific learning goals in mind before a lesson, which any good teacher does, why in the world would we dictate them to students rather than having students participate in the process of formulating them and deciding together what we’re going to explore?”

Professor Dylan Wiliam agrees with Kohn, saying that this dictating of the destination of a lesson to students “spoils” the learning journey itself; and “sometimes, it just makes for uninspired and uninspiring teaching.”

Wiliam also echos Clarke’s point that the learning goal should actually depend on the lesson content. For example, he explains that when “… getting kids to balance chemical equations, I do want every single kid reaching the same goal.” However, when “[reacting] to a poem by D.H Lawrence, I don’t want them reaching the same goal.” And yet, many teachers fear criticism or being caught out in an inspection if they do not maintain the status-quo of Learning Goals.

So what could teachers do instead of dictating the goal to students as soon as they walk in the room? Wiliam suggests that sometimes a question at the start of a lesson can be very effective at engaging students.

For example, I recently began a lesson in which I wanted students to compare the play Romeo and Juliet to the film Titanic. The lesson began with a thought-provoking question written on the whiteboard: “The Titanic was labelled an ‘unsinkable ship’ – so whose fault was the tragedy?” There was a certain level of confusion to start with – to some students the two topics seemed completely unrelated. But after they discussed the question with a partner, we tallied up the responses that were written onto post-it notes and organized them into categories: some blamed the crew, others blamed the engineers, a number of them pointed the finger at the captain, and there was a special column for the unique response blaming “male ego for trying to get to New York in record time.”

I had not expected this response at all! In fact, I wasn’t entirely certain about how the whole lesson would go – though I had a plan. But as I listened to student conversations around the room, I was impressed by how much they already knew about Titanic. To my surprise and delight, one student shared a complex idea with the group: she made the link between the response about male ego and the term ‘hamartia’ that we had recently discussed at length in our study of Romeo’s tragic flaw: his hasty decision-making.

I am confident that had I started the lesson with a Learning Goal and wasted class time by having them copy it down – or even worse, recite it – the inquiry-driven, collaborative discussion at this crucial time of the lesson would not have occurred in such an open-ended, organic way.

It is this spirit of explorative learning that creativity expert Sir Ken Robinson fears is not promoted enough in schools: “Our children and teachers are encouraged to follow routine algorithms rather than excite that power of imagination and curiosity.”

Learning goals are a habit of this algorithm and often serve to narrow the possibilities of a learning experience. These types of teacher-centred approaches harken back to behaviourist teaching where “compliance is valued over initiative and passive learners over active learners” (Freiberg, 1999). It is also tied to the idea that good teaching can be broken down into a recipe of technical, formulaic procedures.

I often wonder what the influential educational reformer John Dewey would make of learning goals. In his 1910 publication How We Think, he states that the role of a teacher is “to keep alive the sacred spark of wonder and to fan the flame that already glows…to protect the spirit of inquiry, to keep it from becoming blasé from overexcitement, wooden from routine, fossilized through dogmatic instruction, or dissipated by random exercise upon trivial things.”

While student disengagement cannot be solely attributed to the practice of oversharing Learning Goals per se, they are a symptom of an industrialized model of teaching in which a feeling of certainty and security is often valued over curiosity. Teachers are hardly fanning the flames of student curiosity when lessons so frequently begin with over-planned, habitual spoilers about the destination ahead, or when educators aim to be so crystal clear in their teaching that they risk stifling the the complexity, ambiguity and wonder of learning for students and themselves.

This is great stuff, Melanie. I think I had some excellent teachers, but this was well before “Lesson Goals”. I remember and treasure special moments, such as the one when my English teacher read us part of TS Eliot’s “Preludes”. He suddenly broke off and muttered, “I wish I could write like that!” That was in 1962, and there are many moments like that which I recall as if they happened yesterday, and which I would cautiously call life-changing.

Keep challenging — it’s incredible that teachers work so much harder now, often to limited purpose.

Cheers,

Barb

LikeLike

Dear Barb! What a pleasure to hear from you and thank you for taking the time to comment. Indeed it does appear teachers are working harder – or at least are being prodded with many more buzzwords and strategies. It’s interesting to reflect back on your own experience as a student and recognize it was the little, organic moments that stay with you. I remember my favourite Drama teacher saying there was a hidden piece of red paper somewhere in the room one day when we first arrived to class. We had to find it. We all searched high and low for this piece of red paper but we couldn’t find it – we got so frustrated by this and kept saying to her “Miss, there’s nothing here, there’s no red paper!” She kept assuring us there was. We kept looking. Then, after about 20 minutes, she informed us there was no paper after all. We sat there angrily and felt hopeless. She then proceeded to kick off a discussion about absurdist theatre. How we felt linked perfectly to the conventions of absurdism: existentialism, no purpose, no meaning etc. WOW! It hit me so hard! I will never forget it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Magisterial in black cassock & boots, tall, thin, pockmarked Brother Remeeus (“Boose”) stepped from desktop to desktop in our class of 30+ Year 9 History boys to illustrate aspects of WW1 power, fear, alliances. We got the point without explicit preamble. I think he overdid things when dangling the lone pacifist Peter Duffy by the ankles from our first-storey window though.

Have you encountered kickback from “eager (read: ambitious) administrators” to your views re Marzarno’s profitable model, Mel? In your old neck of the woods many of us pay scant lip service to it despite being “encouraged to follow routine algorithms”.

LikeLike

Methuselalala – what a vivid memory of what sounds like a captivating learning experience! Sounds like some wonderful ‘hands on’ learning 🙂 Hmm…kickback: not so much in that I’m not regularly asked to share my views, hence my blog/twitter/writing/sharing in other ways. Though I become increasingly emboldened the more I share and learn and read. Such good memories of my time in your neck of the woods – and funnily enough I don’t remember a single learning goal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re not really arguing against learning goals, you’re arguing against the formulaic way they’re used. You’ve said yourself that Hattie and Clarke aren’t arguing for teachers and students to recite them or display them at the beginning of each lesson, just that they should be clear so students know what the goal is – it’s up to the teacher’s discretion to decide when it’s best to make it clear – maybe after a series of provocations (like your Titanic/R&J question). In fact, they argue that learning intentions without success criteria are useless and that the best SC is co-constructed with students. Kath Murdoch recommends framing learning intentions as questions, and this helps to get students co-constructing success criteria and feels more organic. I’m interested to know at what point did your learning steer back to the goal of comparing Titanic with Romeo or Juliet? Or did it not?

This is a controversial point but I think a lot of teachers have used the WALT/WILF/TIB/WAGOLL illustration to pay lip service to the sharing of learning goals and prove they don’t work. In other words, display them, recite them, paste them into books, get the kids to repeat them, then when that doesn’t seem to inspire the kids or to improve learning (why would it??) they say, “there, you see – I told you it doesn’t work!”. With some imagination and creativity it’s not that difficult to build them into a lesson, or a series of lessons, organically (I’m all for sharing learning intentions but I don’t think it has to be for every single lesson). Unless they don’t want to for political reasons.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I really appreciate your point about Learning Intentions. When great ideas become buzzwords all the thought of the why goes out the window. I am huge believer in providing students with learning intentions/goals. With good thought out learning goals – not every lesson – students are able to take responsibility for their own learning and are able to provide feedback to the teacher as to whether they have understood the concept.

Good learning intentions/goals focus on the skills that need to be learned and not on the ideas. When students are involved in great inquiry and creative learning they still need skills that are taught or modeled.

LikeLike

Thank you for this- I loved your writing and your reasoning. You reminded me of an old episode of WKRP in Cincinnati where DJ Venus Flytrap teaches the atom (https://youtu.be/wAN-lnmPlm0). He starts the conversation focusing on the relationship, tells the student what the student is about to learn, and then engages the learner so much that the learner didn’t realize the learning had happened. This is where reflection comes in.

There is no reason for education to be based on a factory model; a creator’s studio might be a better model.

LikeLike

Thanks for this amazing video! I absolutely loved it!

LikeLike

Great piece Melanie! It really highlights the work we’re trying to do in our school. The content is no longer the vital component–instead, how do we use content to develop the the skills students really need–creativity, analytical thinking etc. You could extend this argument to a course syllabus; if we give students a content “to-do” list at the beginning of the year, how can we expect them to want to push themselves outside what they think they ought to be learning. What if, instead, we gave them a list of question to which they can add they’re own. Questions that lead them to consider, analyse and most importantly, be curious.

LikeLike

Alex hello! And thank you for your comment. I am thrilled to hear that this is the direction you’re headed in at your school. I think the teachers and kids will benefit from this approach of more open-ended objectives, particularly as so many jobs now require an ability to wrestle with ambiguity, the unknown or new concepts. Challenges that don’t have straight-forward components. It’s great to hear from you and thanks for taking the time to read and respond! Give my best to all xo

LikeLike

I’m not sure I am ready to buy into this way of going about teaching and learning in the classroom. I am an administrator so it will be hard to convince me otherwise since during the last 23 years I have been preaching the importance of being laser focused on a learning target. In reality it only takes less than a minute to help the students get a an idea of what will be coming at them during the next 90 minutes. Then another minute to remind them in the middle and then yet another minute to close out the day.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment, Jose. As my article suggests, I’m interested in how research is revealing that this kind of ‘laser focus’ doesn’t seem to equate to the type of critical and creative thinking required for the 21st century job market. I’m also skeptical of describing learning as “coming at them” – this reminds me of Howard Gardner’s comment that “typically, school is done to students,” making them passive agents. This is from his book The Unschooled Mind.

In my previous article about Flipped Learning, I write that when learning is “done to” students, or in your words “coming at them”, the process reflects micromanagement, eroding students’ independence and autonomy.

Feel free to read my thoughts on this here: https://lustreeducation.wordpress.com/2018/04/29/is-flipped-learning-looking-at-education-the-wrong-way/

LikeLike

Hi Mel,

Thank you for your article. I really enjoyed it. I will be able to use your ideas to improve practice at our school.

I agree with you. Often, when teachers are told they ‘must’ incorporate a pedagogical trend the validity of it diminishes. It can feel like calling the attendance roll. The use of Learning Intentions, in many classrooms becomes, a simple procedure rather than, as they were intended, a way to help students to become better versed in the language of their learning.

We have been experimenting with visual learning intentions/provocations for inquiry maths lessons in our primary school. Sometimes we write it and refer to it throughout the lesson, while other times it is more powerful to ‘reveal’ it as a lesson closure. We find they are of greater value when written as an inquiry question like, “What ways do the numerals face?” (Year 1) or “What’s so special about prime numbers?” (Year 5). I suppose we endeavour to use them to pique curiosity rather than list curriculum content. (I’d better check that all our teachers know this!)

Since using our version of the ‘Learning Intention’, I have noticed an improvement my student’s ability to have learning conversations and in my own use of inquiry dialogue. Our maths classrooms are busy and -during a really engaging inquiry investigation – a little messy. I have had Year 1 kids remind me of our learning intention when our learning goes off on a tangent! That’s when I like them the best – when the kids can say “We didn’t do much of… today, but we did….”

Having read your piece, I’ll set about making sure our teachers feel more liberated in their use of learning intentions and the reasons for and against them.

Thanks again,

Anna

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Anna,

Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts with me! This is a really cool comment to get in my first week back at work. I agree with you that when a pedagogical approach is a ‘must’ its validity can diminish, sometimes taking teacher autonomy along with it. Obviously clarity is good, but if it clouds the curiosity, or drowns it with teacher-talk, it’s the kids who lose out. I love that you’re using questions in the inquiry maths lessons – and of course in those really engaging lessons things can get messy! Your staff are lucky to have a leader who is clearly very passionate and open to questioning classroom practice. Have a great term!

LikeLike

Hi! Any chance you could cite your references for you direct quotations?

Thanks so much 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Michaela, thanks for reading! I haven’t cited these, but linked to the youtube interviews where I go them – I assume you mean the Hattie quote? Here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CygTwWsoXfE

It took a lot of research to find that!!!! Hope it’s useful.

LikeLike

Link to “It’s Learning Intentions, Jim, but not as we know them…”

https://victorianprofessionaldevelopment.wordpress.com/2022/08/10/its-learning-intentions-jim-but-not-as-we-know-it/

LikeLike